TGH, Special Leap Day Edition! Time to take the plunge

"30 Rock," Adar and the whole time-addition thing

Hi and welcome back to Torah Goes Hollywood. We're coming at you a little earlier this week because it's a special day: it's Leap Day! February 29, that quadrennial event to ensure that the solar calendar remains a nice round 365. Because we Americans only like quarters in our football and frat parties.

As it turns out notions of the calendar and man's intervention in same are also very Jewish. And wouldn't you know it? This solar Leap Day is happening in a lunar Leap Year, as we're deep in an Adar Aleph that's about to start all over again with Adar Bet. Why have one Purimy month when you can have two? So we'll look at that as well. And may just slip a little parshah past you too.

For last year's Ki Tisan glimpse at how movies about cult figures explain the Golden Calf, ride on here. And for a view into how horror movies reflect on the Israelites' bad decision-making, slash this way.

And the general archive? It’s right here.

Let's start hopping.

--

We are living in a magical moment: A solar leap day is happening at the same time as a lunar leap year.

This has happened only once before in the past 16 years and won't happen again until 2052. February 29 and Adar Bet just don't coincide very often.

That's probably a good thing. Because for all their superficial similarities — both expand the calendar to balance it out — there are some pretty meaningful differences between the two forms of leap.

Let's start with Leap Day. Julius Caesar added Feb 29 to the calendar circa 49 C.E. because the actual length of the solar year was 365 1/4 days. So every four years we add 24 hours, much easier than adding six hours every year. Some modest tweaks and other traditions came in the centuries that followed. To wit: the Greeks believe it's bad luck to get married on Leap Day. (Fewer anniversary gifts?)

Indeed, the notion of this day is inherently one of addition, of superfluity, of living outside the normal calendar. Legally, this manifests with birthdays — someone born on Feb 29, as Aunt TGH is, doesn't mark their official birthday for age-related benefits until March 1 in non-leap years. That makes sense, as the completion of the 365-day cycle doesn't happen until then. February 29, in this calculus, isn't real: sure, you were born on it, but it's March 1 that matters.

Conversely, someone born on February 28 in a non-leap year would not mark February 29 as, well, anything. They were born on a day, and they mark that day, and that added day afterward means nothing to them. (Technically someone born on March 1 in a non-leap year should mark their birthday on Feb 29 in a leap year, but I'm not gonna be the one who tells a person they're a day older.)

Culturally, too, Leap Day has been expressed as a bonus day that exists outside of the calendar — and perhaps even outside the realm of natural law itself.

The most resonant Hollywood comment on this comes in the "30 Rock" episode "Leap Day," which aired on Feb 29, 2012. The episode (you can read about it came to be here) has the entire TGS cast and crew celebrating a (clearly-invented-for-the-show) holiday of Leap Day. On such a day a Santa Claus-like figure named "Leap Day Williams" materializes to hand out candy; everyone wears blue and yellow; and people are encouraged to take chances because the day floats outside of time. (Jack, Liz and Tracy all have eventful journeys.)

There's even a fake movie within the show, starring Jim Carrey and Andie MacDowell, about a guy named “Leap Dave Williams” and the power of Leap Day.

From "30 Rock," of course the wellspring of all cultural knowledge, it becomes clear what Leap Day is, and isn't. It is a day of possibility and transformation, a day on which we are unshackled from the normal because we live outside of the normal flow of time. As MacDowell says in the ersatz movie: "Nothing that happens on Leap Day counts."

Now let's swing to the Jews. The Hebrew leap year was conceived during Talmudic times. As the tractate of Sanhedrin notes, time needs to be added to the calendar to keep Passover from migrating out of the spring. The lunar year is 354 days and the solar 365, so if there wasn't some correction every few years, we'd wind up celebrating Passover in the fall half the time — it would move throughout the solar calendar like Ramadan does. And the Torah says of Passover "keep the springtime season."

So a month is added every two or three years to reset the calendar back 30 days. And, the Talmud in Rosh Hashana adds, since the main purpose is Passover-based, the month to add is the one right before it: Adar.

This has the added benefit of allowing the leaders back in the day who were deciding on the extra month (back before calendars were fixed) to take matters all the way up to the cusp of Passover to see if they needed to reset that year. So during Talmudic times the rabbis would get to the end of Adar and decide, based on how imminent spring was, if a second Adar should be added, delaying Passover.

All of this seems to reflect a similar notion as Leap Day: you need to balance out the calendar, so you add extra time every few years to do it. The first Adar is the real Adar, like Feb 28 is the real end of February. And Adar II is, like February 29, the added period, the bonus that exists outside of time.

Except...

Somehow the second Adar is the "real" Adar.

Even though it is clearly the added month, the month decreed at the last moment by rabbinic fiat, Adar II takes on the significance of the real Adar, relegating the FIRST Adar to the one that exists outside of time.

A variety of laws point to this. The most obvious is that Purim is not celebrated until the second Adar. If the first Adar were the actual month and the second the add-on, it would be reversed. But the mishna in Megillah says we read the Book of Esther and give gifts to the poor in the second Adar; there's a question if someone who did so in the first Adar even fulfilled the mitzvah.

Other halachic opinions also underscore this. The Talmud in Nedarim notes that a vow-maker who knows about both Adars and refers just to "Adar" in making their vow is presumed to be referring to the second Adar. Perhaps the most eye-opening opinion comes from Rabbi Avraham Gombiner, the 17th-century Eastern European rabbi known as the Magen Avraham. The Magen Avraham says that a child born in the Adar I of a leap year whose bar mitzvah is now also happening in a leap year actually celebrates their bar mitzvah in Adar II.

That is, even though they complete the full 13-year cycle in the first Adar — Adar I to Adar I — the power of Adar II as the real Adar (and the ethereality of Adar I as the non-Adar) militate for delaying the bar mitzvah a full month.

This is a philosophically powerful statement. It basically says that Adar II, a month added by humans, is so powerful we actually go out of our way to abide by its dictates even when there is every reason to follow Adar I. And that Adar I, the original and actual month, is so outside of time that we don't count it even when a person reaches a milestone on it.

Needless to say, this is a complete inversion of Leap Day. There the human-added day of Feb 29 is the day outside of time and the original day of February 28 the normal one. In Judaism it is — surprisingly — reversed. In Judaism the original month of Adar I is the month out of time and the human-added month of Adar II is the natural month.

In Judaism we actually erase the natural date in favor of the mankind-added one.

This seems like a radical departure. And an illogical one. Let's face it — the solar approach makes a lot more sense. The added time should not be more real than the original time.

Unless we understand why we're adding it in the first place. Because think about it: Caesar added an extra day to compensate for the calendar — to make life more convenient. We had six extra hours, we couldn't leave it dangling, add a day every four years. A perfectly fine goal. But hardly a noble one.

The added month of Adar, however, is for an extremely noble purpose. It is a way of ensuring that a commandment is kept. It is a way of ensuring that the spirit of Passover as a spring holiday of renewal is kept. This isn't leap time for calenderical balance; it isn't leap time so we don't have the annoying feature of six extra hours every year. It is leap time to make sure a holiday is properly experienced. It is leap time to ensure a holy alignment — that Passover can be in spring.

That kind of addition has power, the Talmud I think is telling us. Such an addition has SO much power it becomes more powerful than what was built into the natural world.

That is the power of man — that is the humanist message, I think, of Adar II. That man's willingness to take a misalignment problem into their hands and fix it is not only allowed — it actually creates something stronger than what was there before. Time is physics. But the calendar is man's to shape. And when he does it for the right reasons, it is both encouraged and has tremendous force. But it does have to be for the right reasons.

Our portion this weekend of Ki Tisa has a theme that surprisingly echoes all of this. It is a theme of man adding. Or, more specifically, the dangers of man adding.

The portion begins by describing the half-shekel that is to be given for the Tabernacle, famously decreeing in 30:15 that "the rich shall not give more and the poor shall not give less."

The Ibn Ezra notes of the rich clause "the reason is because it's atoning for the soul." Adding as a flashy show of beneficence — taking matters into one's hands for the wrong reason — is a corrosion of our soul, a corruption of the power man has been given. We are empowered to add — we do it every few years with Adar Bet. But we must do it for the right reasons.

And indeed the latter part of our portion goes on to give the example par excellence of man adding for the wrong reasons, as the Israelites pull jewelry off their bodies and toss it into the fire to create an additional god.

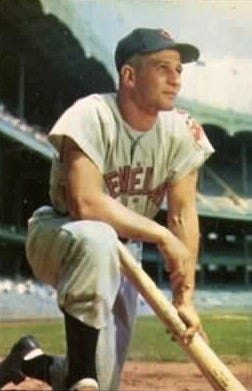

As I was writing this post I happened to be thinking about Al Rosen, a sports hero to Jews everywhere. Rosen (nicknamed the "Hebrew Hammer") was along with Hank Greenberg one of the first great Jewish baseball players, prefiguring Koufax, Lieberthal, Green, Braun, Bregman, Fried and so many others.

A mid-century Cleveland Indians slugger — he won the AL MVP award and home run titles and later was a top GM — Rosen had a knack for doing things the noble way. He served in the Navy during World War II. When he took added action, it was always for the right reason. He refused to play on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur (inspiring Koufax to do the same).

And he was not about to let anyone get away with anti-semitism, which he faced plenty of. When Rosen was called slurs by opposing players, he would often stop play and challenge the player (he was an amateur boxer). "There's a time," he said in a 2010 documentary, "that you let it be known that enough is enough." If Rosen undertook added action, it was always for the right reason — to stand up for his identity and connect to his Judaism.

Rosen was born on Leap Day, and today would have been his 100th birthday.

Thank you, as ever for reading, and have a meaningful Leap Day and a good weekend.