Hey, it's Torah Goes Hollywood again, the place where you get some insights on the holy writ and gain some movie knowledge besides. Or maybe it's the other way around. Either way, we're happy you're here.

This is the week of The Ten Commandments. Did you know that the film “The Ten Commandments” played an astonishing 18 months in select theaters before it even entered wide release? If that happened in today's era — millions of people watching the same thing month after month such that time lost all meaning — we'd call it a pandemic.

Anyway, you know the drill by now. You can read past posts here. Tell your friends to subscribe here. And please, spread the gospel — er, mesorah — of Torah going Hollywood.

Now on to the show.

—

The story of Yitro that opens his namesake portion is — in contrast to the havoc, plagues and Michael Bay-level destruction that precedes it — kind of a sweet one. (Yeah, we're calling him Yitro, not Jethro, in keeping with one of the few cardinal rules we have here at TGH, which is to stay away from associations with '70's flute-rock whenever possible.)

Yitro shows up after a long while to hear what his son-in-law Moses — or his brother-in-law, as scholar David Silber suggests — has been up to. Moses fills him in on all the miracles that went down as the Israelites fled Egypt. Yitro is duly impressed; though a priest of another religion he, like both a moth and Hank Williams, sees the light. Yitro then pronounces God as superior to all the other gods. Alright, so a proud declaration of monotheism it is not. Still.

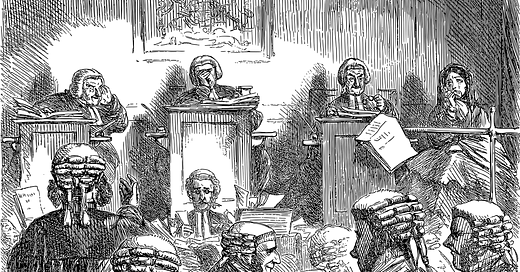

While he's dropping by, the Priest of Midian does a helpful thing and hears out Moses on a problem gnawing at him. Moses has been looking a little worse for the wear hearing all the disputes of the Israelites from morning to midnight, teaching them the laws and adjudicating their disagreements. And who can blame him? He's running pretty ragged. Moses can barely stand from all his instruction on these legal questions. But what else can he do, Moses asks Yitro. The people need to learn.

Yitro returns with a reasonable suggestion. For smaller matters, he suggests, Moses should appoint a whole bunch of other judges — a kind of judicial mini-me's — to dispense wisdom and render judgment. And then when something gets really big and thorny, Moses can be called upon. It's a district court-appeals court kind of setup.

“V’samta aleihem sarei alaphim, sarei mayot, sarei chamishim, v’sarei asarot,” it says in Exodus 18:21. “Put upon them chieftains of thousands, of hundreds, of fifties, of tens.” And that’s exactly what happens. Moses institutes this system. He is grateful, and wakeful. All is well. We can get onto the portion’s main business of receiving the Torah.

Except the story doesn't belong here. I don't mean that in a thematic, figurative, inclusion-y, kind of a way. I mean that literally. Yitro has come after the people are already encamped at Sinai, we’re told. But the process of encampment doesn't begin until the next section. It also happens “on the day after” — after Yom Kippur, when Moses had received the tablets for the second time, Rashi notes. It seems pretty clear the Yitro ditty happens after the Torah is given, not before, as our portion confusingly implies. A bungle in the jungle, indeed.

So why is it placed here? Why before the most important moment in the entire five books of Moses do we have a seemingly random story about Yitro showing up to advise on a bunch of judges? Rabbi David Kimchi, the Medieval French commentator known as the Radak, has an intriguing theory. He points out that it’s in this spot, right after the Israelites had fought the Amalekites at the conclusion of last week’s portion, to show that there are different models of non-Israelites. There are the ferocious exploiters, trying to attack when people are at their weakest, like Amalek. And then there are the Midianties, or at least Yitro’s particular tribe of Midianites, that come in peace and leave in peace and generally show that not all strangers are hostile and in fact worth engaging with and even worth listening to.

It’s a beautiful globalist message. But I’d also propose something else. The story is coming here not because of Amalek. In fact, it’s not coming here for what precedes it but for what follows. It’s coming here specifically before the Israelites are given the Torah. And it’s not a needless digression but integral to it.

To explain why, though, I have to first turn to another eager entity awaiting revelation from a supernal being.

That would be none other than Danielson and Mr. Miyagi.

In "The Karate Kid" circa 1984, Daniel is champing at the bit for Miyagi to show him the secrets of karate when the wise one puts him through a variety of meaningless tasks. As Ralph Macchio’s character (the movie is a touchstone to those of us of a Gen X vintage; we'll try to forgive the rest of you) begs to learn, Pat Morita’s guru makes him do chores. “Paint the fence.” “Wax on, wax off” the car. That sort of thing.

Daniel just wants to receive the wisdom of karate. But Miyagi is having none of it.

At one point Daniel gets frustrated. Mr. Miyagi tells him that actually he has been learning, Daniel responds snarkily. “I learned plenty. How to sand your decks, maybe. Wash your car, paint your house paint your fence. I learned plenty. Right,” he says, dripping with sarcasm. (You can watch the scene here.)

Miyagi sets him straight — he stages offensive and defensive fight maneuvers. And sure enough, all the motions and discipline learned during these exercises — the tight rotations of his hand in one direction then another of the wax-on-ing, the sharp stabbing upward and downward of the fence-painting, all of it — gives him the tools he needs. Mr. Miyagi, while seeming to delay, has been teaching Daniel all along. This isn’t pointless lollygagging to the revelation. It is necessary prelude to it. Before Daniel can learn the actual moves, he needs to understand how much they affect every part of his life. That’s the real lesson. Karate is not some lofty, abstract notion; it’s down here with us at every moment.

That point internalized, Mr. Miyagi tells Daniel to come back tomorrow, when he will reveal the deepest essence of karate — a matan martial arts, if you will.

This all feels pretty relevant to the Yitro story. The Israelites are about to receive the Torah in a ceremony of massive spectacle. They are warned to prepare themselves, to wash, to stand back., And then thunder and lighting literally begin to manifest. They are ready for all this to happen.

But the text wants to do something for all future generations reading this: It wants to slyly teach us a lesson first. All of this spectacle, all coming from God via one man, can make it seem like Torah wisdom is a lofty, abstract thing — important, sure, but not down here on earth or much integrated into our daily lives.

So there’s a low-key insight — a story about how it’s unfolding here with all of us, available on a very intimate level. “V’samta aleihem sarei alaphim, sarei mayot, sarei chamishim, v’sarei asarot.” “Put upon them chieftains of thousands of hundreds of fifties, of tens.” An entire group of judges and teachers, down to the smallest of groups, all here ready to teach and learn with everyone else.

This isn’t pointless lollygagging to the revelation. It is necessary prelude to it. The Torah and the Ten Commandments that encapsulate it might have seemed like the domain of a singular entity. It appears the opposite of a democratic system, of something with popular resonance. Yet with thousands of everyday tutors taking part in it, it is down here on the ground with us all.

It’s a subtle imparting, like Miyagi’s. But by placing the story here, the text is quietly telling us not to think of the impending revelation only as the epic show we’re about to see. It’s telling us to think of wisdom as something happening with our friends on the regular too.

In fact, you might even suggest Yitro is teaching Moses his own lesson by-the by — slyly telegraphing to him that Torah doesn’t need to be taught by one person but can be plumbed by large groups of everyday people; he’s serving as his own Mr. Miyagi to Moses’ Danielson.

When it comes to wisdom, the portion says, it’s important to have a performative reveal. It may be just as important, though, to get it across in little details, to work it into our daily lives, to have it come from anywhere.

Thank you for reading, and for unexpectedly reminiscing about Mr. Miyagi.